A Millennium Under Waves, A Millennium in Fire

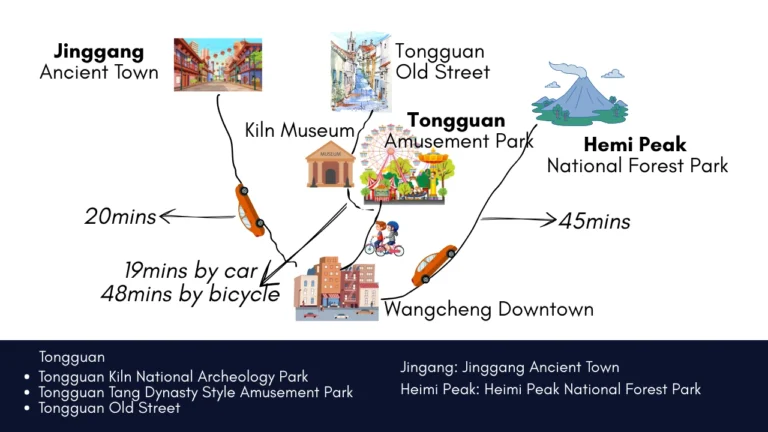

Tongguan feels at once real and unreal. The skyline is crowned by a grand Tang-dynasty–style city, rebuilt in ancient fashion, all high gates and earthen wall, where workers stroll in Tang-era robes. A legendary shipwreck is brought to life in a theatrical show run by a U.S. company, with waves of light and sound retelling an ancient maritime tragedy, drawing young crowds in search of spectacle. Yet just six minutes away by car, the thousand-year-old street lies quiet, steeped in genuine history, where pottery workshops still breathe the same smoke and clay as they did in the Tang. Locals joke that “even Grandma’s foot basin is an antique,” and in Tongguan, you almost believe it.

From Titanic to Black Stone Shipwreck

In 1998, two very different ships captured China’s imagination. One was the Titanic, whose film release was so popular that audiences queued until two in the morning to get a seat. The other ship—lost for over a thousand years, nearly ten times longer than the Titanic—was discovered in the waters off Indonesia’s Belitung Island, instantly seizing the attention of China’s archaeological and media worlds.

Its story begins not with a captain or a storm, but with a conversation in a cement factory. In 1996, German entrepreneur Walter Fang was chatting with one of his Indonesian workers when a tantalising detail slipped out: somewhere in his homeland’s waters, ancient porcelain lay buried beneath the sea.

The Day the Black Stone Shipwreck Emerged

That single remark set Fang on a two-year quest. He travelled to Indonesia, founded a salvage company, and combed the ocean in search of lost worlds. In 1998, near Belitung Island, he struck gold—literally and figuratively. Beneath the swell lay a Tang Dynasty merchant ship, its hold bursting with 67,000 artefacts.

Locals called the wreck the Batu Hitam Shipwreck—batu meaning “stone” and hitam meaning “black.” We refer to it as the Black Stone Shipwreck, named after the dark reef that claimed it. Legend has it that the ship, carrying bronze mirrors from Yangzhou and porcelain from the Changsha kilns, sank in Indonesian waters after changing course to avoid pirates and striking a reef. The waters were said to be haunted by an Island Curse: a fisherman who uncovered treasure was killed by a greedy antiques dealer—yet the dealer’s triumph was short-lived, for pirates soon wiped out his entire family.

Why the Black Stone’s Cargo Matters to China

Among the 67,000 pottery artefacts, more than 50,000 of them are from the famed Tongguan Kiln of Changsha. Many museums in China, including the Hunan Provincial Museum, sought to negotiate the return of these artefacts to China. However, Walter Fang set a high price—USD 40 million for the entire collection, with no option for partial purchase. This was far beyond the purchasing capacity of Chinese museums at the time.

Eventually, a wealthy Singaporean philanthropist donated a large sum to help the Sentosa Group in Singapore acquire the entire collection. Today, all the recovered artefacts from the shipwreck are housed in the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore.

Fortunately, when Fang sold the collection as a single lot, he kept a small portion for himself. In 2017, 162 of these precious pieces finally returned to their homeland, and they are now on display at the Tongguan Kiln Museum in Changsha.

Beyond the Wreck: Tongguan’s Living Kiln Culture

But what truly makes Tongguan a place of treasure is not just the shipwrecks, but the stoneware craftsmanship passed down through generations. Most descendants of these artisans are based in Tongguan Old Street, about five kilometres north of the Tongguan Kiln Museum. The masters here all come from families with long traditions in stonewear. Rooted in Tongguan for generations, these artisans have shaped clay with the same hands as their ancestors, their lives intertwined with the rhythm of the kiln. Having never left to study or trade in distant cities, they still speak in the warm, familiar tones of the local dialect.

The Science Behind the Craft

In the world of pottery and porcelain, decorative vases and ornamental pieces are usually made of porcelain, prized for its translucence and sheen. Containers for storing food, tea, wine, or vinegar, however, are more often made of stoneware, as the clay gives them excellent breathability. For example, when storing tea, the dense structure of glass or porcelain can cause unwanted fermentation, whereas pottery helps preserve freshness. Stoneware vessels are ideal for brewing black, dark, or green teas. For example, the Purple clay teapots are known for the principle of “one pot, one tea,” but stoneware is both breathable and resistant to absorbing flavours from different teas. This is because stoneware is fired at temperatures over 1,200°C, which preserves its porous nature. Porcelain, although also fired at high temperatures, becomes vitrified—like glass—and loses breathability. This is why everyday households in China have long preferred stoneware for storing tea, salt, sauces, and vinegar. Moreover, while broken porcelain can easily cut the mouth, chipped stoneware can still be safely used, and thrifty families often continue to do so.

One Comment